To Be a Blessing:

Lessons on Justice and Mercy from the Old Testament

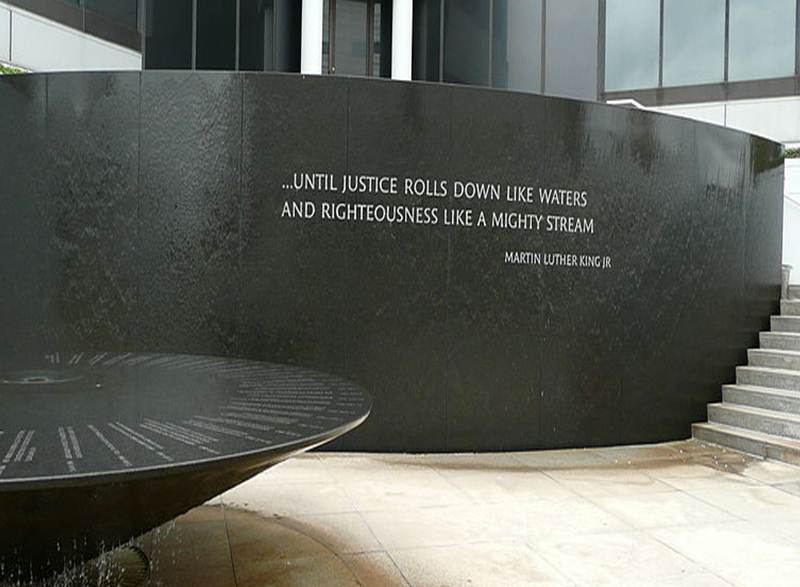

One sentence flows across a black granite wall in Montgomery, Alabama: We will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream. Paraphrased from the book of Amos and engraved on a Civil Rights monument, this statement crosses millennia to underscore unchanging lessons for humanity. Today, I will look at three Old Testament teachings about the way mercy, justice, and blessing contribute to safe and benevolent communities: Abraham’s blessing, the Sabbath commandment, and Isaiah 58. I will then share some thoughts about how these notions of justice, mercy, and blessing can affect us and our Adventist communities today. You will probably note that my focus on the concept of justice is an emphasis on “justice for,” not “judgment against.”

After sin, after the Flood, after the tower of Babel, God began to rebuild an intentional human community. He called Abram and said, ‘I will make you into a great nation, and I will bless you; I will make your name great, and you will be a blessing’ (Genesis 12:2). He and his descendants were to be a blessing, wherever they went, with whomever they interacted. Their success and the longevity of their extended community depended on their choice. It was that simple: Be a blessing. It was that difficult.

Later, in restructuring the Hebrew community at Sinai, the principles shared with Abram became more concrete. The fourth commandment of the Decalogue (Exodus 20:4-8) encapsulates some of them. The seventh day is the Sabbath. From grammatical emphasis in the original text, I infer a level of importance placed in the lessons it teaches. The commandment was a gift of the God who had rescued them from bondage and protected them from a scorching desert sun. He lit the darkness at night and fed them in the morning. With the Sabbath, God offered yet another blessing. He reminded the community that He would make sure they were fed and that their crops and produce would be safe in the twenty-four hours they were not “in control.” Israel was to learn another aspect of trusting God.

Nourished by this blessing, God’s Hebrew community was to respond on the seventh day by being a blessing, by showing justice and mercy not only to those who were vulnerable among themselves but also to those under their power. I believe that lesson was to be infused into Israel’s consciousness and actions. Children, servants, animals, and the sojourner who was “within their gates” were equal recipients of the mercy of God and should be equal recipients of the blessing of community. The future of the young nation depended on their understanding of, and choice to live, this lesson.

Hundreds of years and many wrong decisions later, Isaiah began to write. His work is packed with critique, counsel, and promise. In Chapter 58, the conditions for community blessing are concise:

♥ Loose the bands of wickedness; undo the thongs of the yoke. (vs. 6)

♥ Let the oppressed go free; break every yoke. (vs. 6)

♥ Share your bread with the hungry; bring home the homeless poor. (vs. 7)

♥ Cover the naked. Don’t hide from your family. (vs. 8)

♥ Take away from the midst of you the yoke, the pointing finger and malicious talk. (vs. 9)

The wickedness, described in preceding lines, includes:

♥ Seeking own pleasure; oppressing workers (vs. 3)

♥ Quarreling, fighting, and hitting with wicked fists. (vs. 4)

I find it interesting that the justice and mercy focus of this week’s lesson was also the focus of God’s accusations. Wickedness was a lack of justice for oppressed workers. Wickedness was a lack of mercy played out in the field of neglect and violence (quarreling, fighting, hitting). While this message was certainly to be heeded by individuals, God’s focus, through Isaiah, was also on the community.

We can think of ancient Hebrew as a “visual language.” It was highly metaphorical and, as we know, metaphors have hidden layers for the observant reader and listener. The brass serpent on the cross meant more than antitoxin in a crisis. The sanctuary in the desert meant more than a ritual religious bonding. Jesus, talking to the woman at a Samaritan well, discussed more than liquid refreshment.

I am certain that most readers or listeners to Isaiah’s scrolls could think of instances when they had seen opportunities to share their bread with the hungry, care for their families, and clothe the naked. I believe they had also seen the effects of “the pointing finger and malicious talk.” I believe that Israel had some understanding of the extended meanings of Isaiah’s pronouncements.

Our twenty-first-century community of Seventh-day Adventists has much to learn from these Old Testament pictures. If we are to be the ones who “raise up the foundations of many generations…are called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of streets to dwell in,” if we are to “delight in the Lord” and “be fed with the heritage of Jacob” our father, we need to embody the lessons described in the texts we read this week.

Since we claim to be spiritually descended from Abraham we also have his mission: “You will be a blessing.” A blessing to whom? The texts in Genesis don’t restrict that blessing to particular individuals, populations, beliefs, systems, or lifestyles. There was no limit. There is no limit.

If we are to bless like Abraham, we need to be open to the world. That’s difficult. Do we draw limits with those for whom we seek justice and mercy and blessing? With liberals? Conservatives? The people who might be converted if we are nice to them? Our family? Immigrants? Refugees? Hard workers? Slackers? The lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender Adventists with whom we come into contact? The same group if they are celibate? Our church leaders? Our church leaders if they agree with us? The people of our town or province or country? The Adventists who are in favor of women’s ordination? The Adventists who are not? The Adventists who believe in a six-day creation? The Adventists who do not?

Daniel Duda recently said, “The church exists for one purpose: to create a community of unconditional acceptance.” I go over the list of people and groups in my purview and realize how different my life, my church, and my community would be if we lived these words and Abraham’s promise.

Under the umbrella concept of Abrahamic blessing, there are details. The Sabbath commandment and Isaiah’s sermon teach that we are to have rest if we allow that rest to include those who are vulnerable to us. At Sinai, the list included children, servants, animals, and guests harbored within Hebrew homes from desert dangers. I consider 21st-century corollaries.

All over this world today, untold numbers of children live in dangerous or abusive circumstances. Those contexts can range from poverty and neglect to sexual abuse or life in the killing fields of Syria. Resiliency theory teaches that if such children have one person, just one, who is safe, caring, accepting, and nurturing, that child has a high chance of building a healthy life. The one person can be as varied as a parent, school janitor, youth leader, bus driver, or neighbor. There is power in one. Do not underestimate the effect you can have on one life.

From another perspective, we must think carefully about how we will be with the children and youth we encounter. How do we share mercy toward, and insist on justice for, the children who tell us they have doubts about God, use drugs, are having sex, are gay or transgender, have parents who abuse them, are angry in Sabbath school, or run away from the community they have known? What about the children who say they are religiously conservative and want to know how to be with others? How will we be a blessing?

We may not have live-in servants. We may have cleaning help. Or people who mow our lawns. We may have people on our committees at church. We may have employees or teams we supervise. We may have influence over policies and procedures. We may be elders or deacons or denominational administrators. The lessons of mercy, justice, and blessing apply to all of us. How do we live them?

In this 21st century, the meaning of “stranger within our gates” is broad and varied. What is clear is that the person being described is not personally known to us and can come from any place. Who is this stranger? Is it a fellow traveler in our spiritual world? Is it a drunk? A military veteran? A child? A refugee? Are they fragile because they have eating habits or a lifestyle we would question? Are they a teen who was kicked out of their house because…? Are they just lonely? Are they old? What do they mean to us as individuals? To us as a local spiritual community? To us on the larger scene? Do we feel safe having strangers in our home? In our country? How do we deal with those we don’t understand who want to find sanctuary in our church? How broad are our gates? How do we live the mercy, justice, blessing that are our Abrahamic mandates?

Adventists have done a great job of literally following Isaiah’s instruction to clothe the naked. I remember folding second-hand garments in third grade. They went someplace beyond my geographic knowledge. I remember the days Dorcas rooms opened their doors and the days volunteers boxed emergency clothing shipments to disaster areas. Being physically naked is a vulnerable way to live. So is being socially naked—our secrets out for everyone to see. The Samaritan woman’s solo trip to the well at the hottest time of day shows the life-threatening consequences of being socially naked. What about the suicidal teenager who has his secrets blared across social media? How about the times we have publicly failed in a church duty? Or a job? Or invested our retirement funds in a Ponzi scheme? Or made investment mistakes with church resources? How would you like your church community to be just with you, to be a mercy to you, to be a blessing for you?

I have never heard a sermon about the promise that includes “if you take away from the midst of you the yoke, the pointing finger and malicious talk.” I have never seen church discipline for it. But I have seen pointing fingers and malicious talk destroy individuals, relationships, and communities. I think a lot about Ellen White’s quote, “Do not set yourself up as a standard. Do not make your opinions, your views of duty, your interpretations of scripture a criterion for others and in your heart condemn them if they do not come up to your ideal. Do not criticize others, conjecturing as to their motives and passing judgment upon them.”*

At the moment, we Adventists are dealing with at least three divisive issues: women’s ordination, sexual diversity, and creation. We also live with cultural differences, family stressors, abuse of various kinds, refugees, hunger, and war. We are a cauldron of viewpoints, opinions, values, hopes, and fears. As he considered how pastors care for their communities in the midst of these crises, Gerard Frenk wrote, “In such a cacophony we run the danger of not hearing the two most important voices: our own and the voice of someone who, in the middle of all the noise, asks your attention for his or her personal story.”** Justice, mercy, blessing are individual acts that affect larger communities.

We are a “people of the Word.” We say we want to follow that Word. As in the issues mentioned above, a challenge to our community relationships often comes when our readings of texts in the Word differ. Even our theologians and scholars disagree on exegesis and hermeneutics. Given our conundrums and the effect they have on our personal and corporate communities, I very much appreciate Jeroen Tuinstra’s observation: “When a text has multiple ways to be explained, one chooses the explanation that causes the least harm, shows the most patience, and expresses closely the fruit of the Spirit.”

And the fruit of the spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control. Against such there is no law. Galatians 5:22, 23

Mercy, justice, the fruit of the Spirit.

How will you and I and the even larger “we” live these building blocks of a community of blessing?

NOTES:

*Ellen G. White, Thoughts from the Mount of Blessings, 123, 124.

**Gerard Frenk is secretary emeritus of the Dutch Union Conference. The quote is from his paper, A Pastor Between a Rock and a Hard Place.

***Jeroen Tuinstra is president of the Belgium Conference of the French Union.

Many thanks to Gerard Frenk for taking the time and patience to edit this paper. Much appreciation to Jacquie Hegarty and Carrol Grady for proofreading it.